The Resource Curse: Nauru's Rise, Ruin and Return to Extractivism

- Ronath Wijekoon

- Aug 9, 2025

- 5 min read

In a desperate bid for economic revival, Nauru is betting on deep-sea mining - a gamble that risks irreversible damage for a payout that may never come.

Nauru’s fall from grace is a cautionary tale of greed, foreign-party interference, and the pitfalls of Extractivism. With a troubled past stained by laundering money for international criminal organisations, to their more recent mismanagement of Australia’s detention centres, Nauru has truly become a "Country With Nothing Left to Lose".

However, this was not always the case. Only fifty years ago, Nauru was “The World’s Richest Little Isle”, who found its fortunes with a simple natural resource – guano. Guano, rich in phosphate, was vital for global agriculture and generated a fortune for the foreign companies and nations that oversaw Nauru’s mining operations. By the time Nauru gained its independence in 1968, more than 35 million metric tons of phosphate had left its shores. On paper, Nauru was rich. Government officials would import supercars, charter private planes, and live in opulence. But beneath the surface, Nauru was being strip-mined to its collapse. By the early 2000s, the guano boom in Nauru was well and truly over, and its economy was in a state of crisis. The nation’s trust fund, which should have been brimming with billions of dollars’ worth of guano profits, had a measly $30 million remaining. Today, Nauru is one of the poorest nations in the world, with a quarter of its inhabitants living below the poverty line. The supercars imported by their former leaders lay discarded and rusted across the island as a reminder of their greed and economic mismanagement.

Source: Sven’s Travels, 2018

Nauru’s experience illustrates that resource injustice is one of the many drawbacks of Extractivism and is entrenched across the globe. At the heart of this injustice lies systemic power imbalances and information asymmetries, which leave developing nations particularly vulnerable to exploitative outcomes in foreign-managed mining operations. History seems to be repeating as the Pacific is now faced with a new challenge - the emergence of Deep-Sea Mining (DSM) in its waters. To date, over 20 foreign contractors have flocked to the region, staking their claim and capitalising on the potential lying on the seabed. Once again, “The Country with Nothing Left to Lose” has dived headfirst into agreements and been one of the most vocal advocates for deep-sea mining.

A New Gold Rush Beneath the Waves

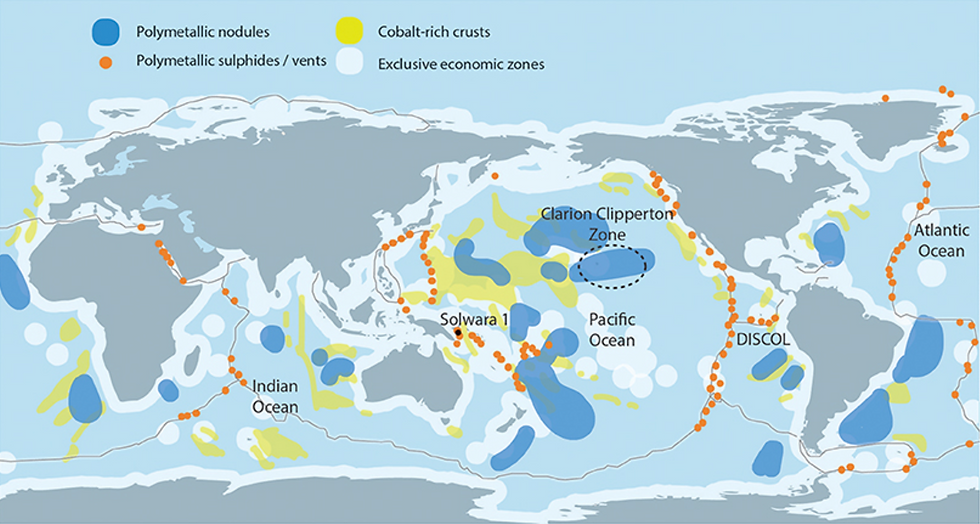

There is no doubt that DSM in the Pacific is enticing. An area attracting considerable interest is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), situated between Mexico and Hawaii. In an area over one and a half times the size of Western Australia, trillions of dollars’ worth of resources lie scattered across its seabed in the form of potato-sized polymetallic nodules containing mixtures of nickel, cobalt, manganese, and copper.

Source: Miller et al., 2018

Mining advocates even emphasise the environmental allure of the CCZ, as it is relatively empty, with one of the lowest biomass levels of any planetary ecosystem. The extraction method proposed for the region is touted as the least environmentally damaging form of DSM, as it operates without drilling or digging. Despite arguments from scientific experts and pleas from neighbouring Pacific island nations, Nauru’s position is clear. At the 2024 United Nations General Assembly in New York, Nauru's President, David Adeang, urged the world not to “let fear and misinformation creep in,” as DSM is an “environmental imperative” for the global transition to renewable energy.

Power in the Pacific: Nauru, The Metals Co, and the International Seabed Authority

The majority of the CCZ lies in international waters and is governed by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), an organisation established under the banner of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Unlike Exclusive Economic Zones, which are free to be exploited by their controlling nation, international waters should be for the benefit of all of humanity in line with the ISA’s purpose and guidance. The ISA has historically avoided the cries of Nauru and other mining advocates; however, after years of negotiations, the ISA is due to adopt a final set of regulations that will govern responsible commercial mining operations in international waters in July 2025.

Pacific island nations have a significant role to play as the new regulations roll out. Any entity interested in engaging in mining activities in the area must be sponsored by a member state of UNCLOS. Given their status as member states and their geographic proximity to the CCZ, numerous Pacific island nations have been courted by international mining companies. This includes Nauru, which is the sponsoring state of Nauru Ocean Resources Inc. (NORI), a wholly owned subsidiary of the Canadian Mining company, The Metals Co. (TMC).

From sponsoring food security projects, education programs and sporting events, TMC has embedded itself with Nauru’s society. Beyond these tokens of appreciation, TMC’s head of stakeholder engagement, Corey McLachlan, has expressed the company’s long-term vision with Nauru as it aims to become the nation’s largest contributor to GDP. The goal is clear: by providing a steady stream of administration fees, mining commissions and tax revenues, TMC believes that it can transform Nauru’s economy.

Source: The Metals Company, 2024

Gold Mine or Fool’s Gold? A Risky Bet on the Ocean Floor

President Adeang has publicly acknowledged the costly mistakes of Nauru’s prior mining ventures, stating that “we made mistakes, and we’ve learned from them”. Despite these words, Nauru’s myopic approach to negotiations with TMC contradicts the most recent academic and economic evidence.

Several studies have concluded that countries engaging in deep-sea mining are likely to receive economically insignificant benefits from both corporate income tax and royalties. On the higher end, sponsoring states are expected to receive A$11.4 million annually, broken down into A$9.7 million from corporate taxes and A$1.7 million from ISA mining royalties. This measly compensation represents under 5% of Nauru’s GDP, and disturbingly, this amount is likely to be considerably lower.

Unlike other nations, Nauru’s sponsorship contract with TMC does not outline a formal agreement with regards to corporate tax payments, rather referencing other paltry taxes and admin fees. Despite this, TMC has given Nauru their word and has committed to paying the current corporate income tax in the country, which stands at 25%. Yet, this commitment carries little practical weight. Given TMC’s substantial accumulated losses and the possibility of profit shifting through methods such as transfer pricing, it is unlikely the company will even generate taxable profit in Nauru.

In its pursuit of economic revival and a return to its former glory, Nauru has aligned itself with an industry that threatens irreversible harm. Deep-sea mining risks destroying marine ecosystems valued at over A$500 billion, with potential climate impacts worse than land-based mining. In a region where climate change and rising sea levels already pose an existential threat, Nauru needs ask itself a question, is the meagre compensation worth the damage that it is abetting?

Comments